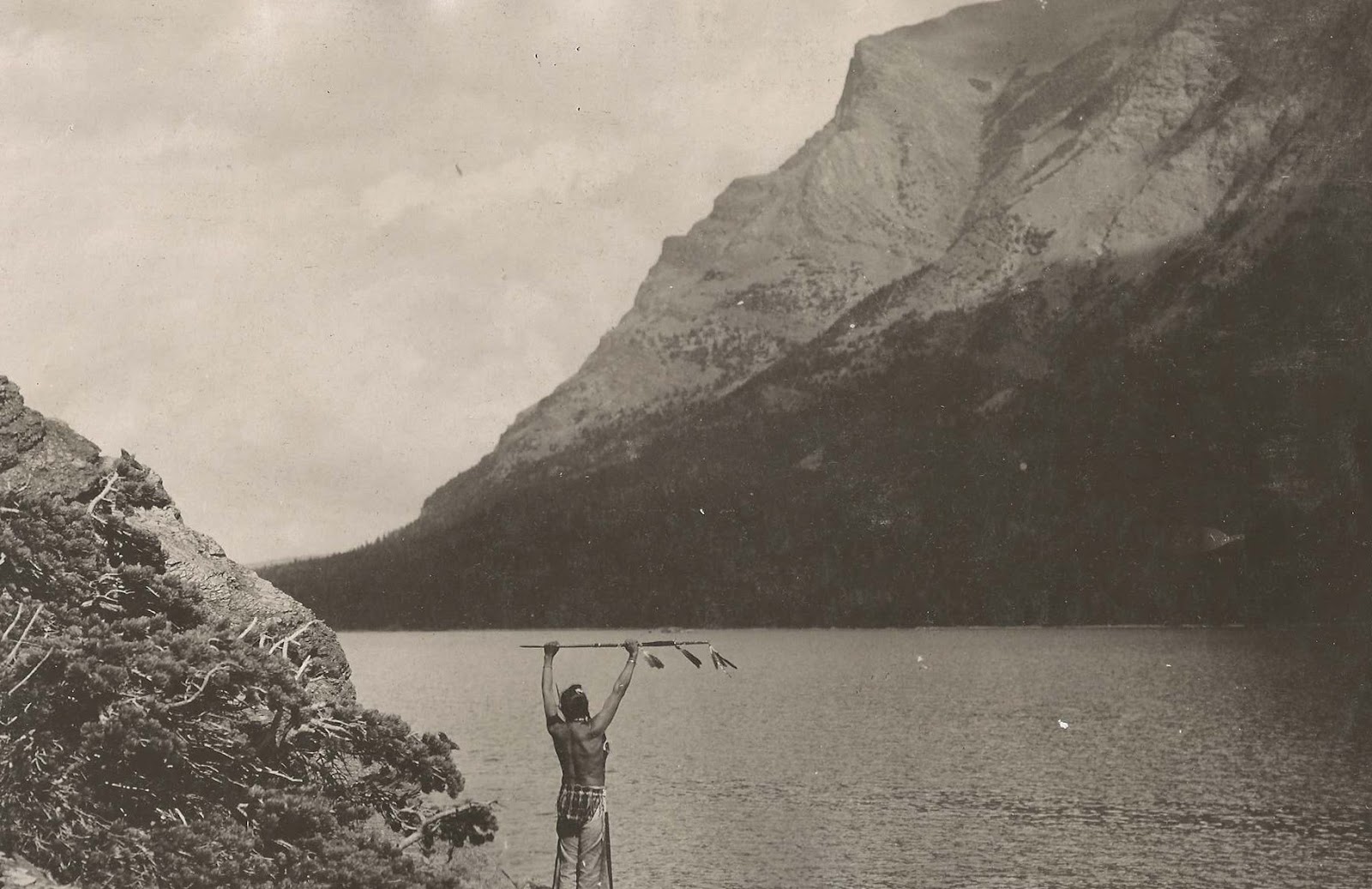

Indigenous tribes of the early Americas were noted for

covering tremendous distances in dense Eastern woodland, stark Plains, and the treacherous

desert and mountain territories of the Southwest.

Yes, many horse-culture tribes covered these vast territorial

empires on horseback, but pre and post-horse many were doing the same vast

ranging by dint of foot travel alone.

These “terrain-eaters” or “earth-walkers” were not confined

to some cardio-blessed cadre within each tribe; we see these feats of distance

and fleet-of-foot speed demonstrated across the board in man, woman, and child.

General Crook during his pursuit of the Apache in

America’s Southwest would remark that entire villages would be up and long gone

from last-known scout-reported locations in a mere 24-hours.

That is, man, woman, and child—young and old—packed camp

and were gone by the time the soldiers arrived.

An entire village could be 70 miles away by the next

day and this is all under load.

Remarkable.

These distance and speed stories are copious in the historical

and anecdotal record.

What makes them additionally remarkable, at least to

my eye, is the concentration of how to walk, lope, run,

crawl, in short, how to move on the planet was given such fine detailed

attention.

In essence, all were “trained” to move efficiently

from a young age.

It stands to reason that a nomadic people would refine

the main mode of travel, just as we pursue the newest model of car.

Walking, Running, & Loping

There is confusion among some who merely read accounts

that the speed of movement and the distances covered must have been made by

running, or at the very least a sort of jogging tack.

This confusion is added to by many calling how the

tribes moved as “Indian Running.”

But this is a bit of a misnomer.

Yes, running was used by tribes—often by the Warrior

class or messengers. Many games and competitions featured the sort of running we

envision when we use the word “run.”

Many of these games are captured in Peter Nabokov’s Indian

Running: Native American History & Tradition. Nabokov’s volume focuses

on the actual running traditions of the Southwest, the Navajo and Tarahumara,

for instance. The Tarahumara also feature in Christopher MacDougall’s Born

to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has

Never Seen.

What these volumes do not capture is the other form of

“running,” what many an early Cavalry journal reported as “That curious

miles eating lope.”

Often, what was referred to as “running” was actually

what we term Warrior Walking, which is an incessant miles-eating walking

pace with its own curious mechanics.

[Western author Larry McMurtry combined aspects of

these Warrior Walkers into a single character, the Indian scout, Famous Shoes,

in the novels Streets of Laredo and Comanche Moon, both part of The

Lonesome Dove series.]

Warrior Walking & Indian Running

There is a vast difference between these forms of indigenous

locomotion. We have detailed these differences in our program Unleaded: Warrior Walking, the Only Cardio You Need for Combination Fighting, Physical Culture and Attacking the Outdoors.

Let us look to one account of the Northern Blackfeet

to observe an instance of Warrior Walking that has mistakenly been termed “running.”

The following is from the reminiscences of Buffalo

Child Long Lance, a North Carolinian of mixed race who adopted into a tribe and

observed the following. [His “outsider” status likely explains the use of the word

“running” to describe what he saw.]

“A favorite race of the Northern Blackfeet, on

sports days, was running from Blackfoot Crossing, now Gleichen, Alberta, to

Medicine Hat and back. That was a distance of about 240 miles. They would start

one morning and return the next day—non-stop and on foot. We always ran our

foot-races barefoot, not caring to wear out our moccasins, and at the same time

wishing to strengthen and toughen our feet. We would tie a buckskin band around

our heads to keep our long hair out of our faces, and pull off everything but

our breech-cloth, and we ran with our hands down at our hips. It was undignified and a sign of weakness to bend our elbows

and run with the hands seesawing back and forth across our chests. After

our races we always plunged into the cold river for a swim.”

Points of Note

·

The mileage, if accurate, is stunning.

Hell, even if we cut that distance in half, stunning for a 48-hour trip.

·

Running barefoot is common in these accounts,

either that or having a surplus of moccasins in one’s pack. [Many mountain men

and scouts would strip moccasins off fallen combatants to store up for just

such long-walk needed occasions.] Kinda puts our obsession with engineered

footgear into perspective.

·

“Running” with Hands-Down—this

is referred to in account after account by Frontier Cavalry observers, this is

what they referred to as a “lope.”

·

This is not an awkward stiff-armed run; it

is a rapid and smoothly paced walk.

·

The Warrior Walking Program goes into

strict detail as to how this straight-arm position was utilized—shoulder

position is mighty key.

“It was undignified and a sign of weakness to bend our

elbows and run with the hands seesawing back and forth across our chests.”

·

Another key observation.

·

In Warrior Walking arm amplitude never

changes and contralateral arm motion never crosses the hips.

·

Inefficient forward momentum forces and a

bit of spinal shearing and added fatigue for the long distances aimed for.

Of course, there is more to Warrior Walking, loping, this

walking form of “Indian Running” than we can get into here. We cover it all in detail

in our Warrior Walking Program, but for our purposes, it is sufficient

and remarkable to observe that a nomadic people put quite a lot of brilliant thought

into how to move across the planet.

It turns the simple act of walking into a work of Warrior

Art.

For more information on Warrior Walking or to get

started on this Old Way.

Info on our other Old School Inspired Conditioning

Available Volumes in The Unleaded Program

·

The Pliant Physique

·

Core Stability

·

Hips Stability

·

GFF: Grip-Fingers-Forearms.

·

The Chest Battery

·

The Back Battery

·

The Shoulder Battery

Upcoming Unleaded Volumes include…

·

Hidden Gems: Stabilizing Muscle

[Pre-Hab, Re-Hab, & the True Core]

·

The Shotgun Muscle Trifecta:

Strengthening the Peripherals

·

The Shock Muscle Trifecta: Ballistic

Motion for Combat Athletes

·

The Tarzan Twelve: Feats to Show Off

What You’ve Built

·

And complete Batterys for Core:

Abdominal Strength and Rotational/Extension Game-Changers, Thigh-Hips-Knees,

Biceps, & Triceps.

·

The Unleaded Female Warrior Program

·

[Each Program is a DVD/Booklet package.]

More Resources for Livin’ the Warrior

Life!

The Rough ‘n’ Tumble Raconteur Podcast

Comments

Post a Comment