|

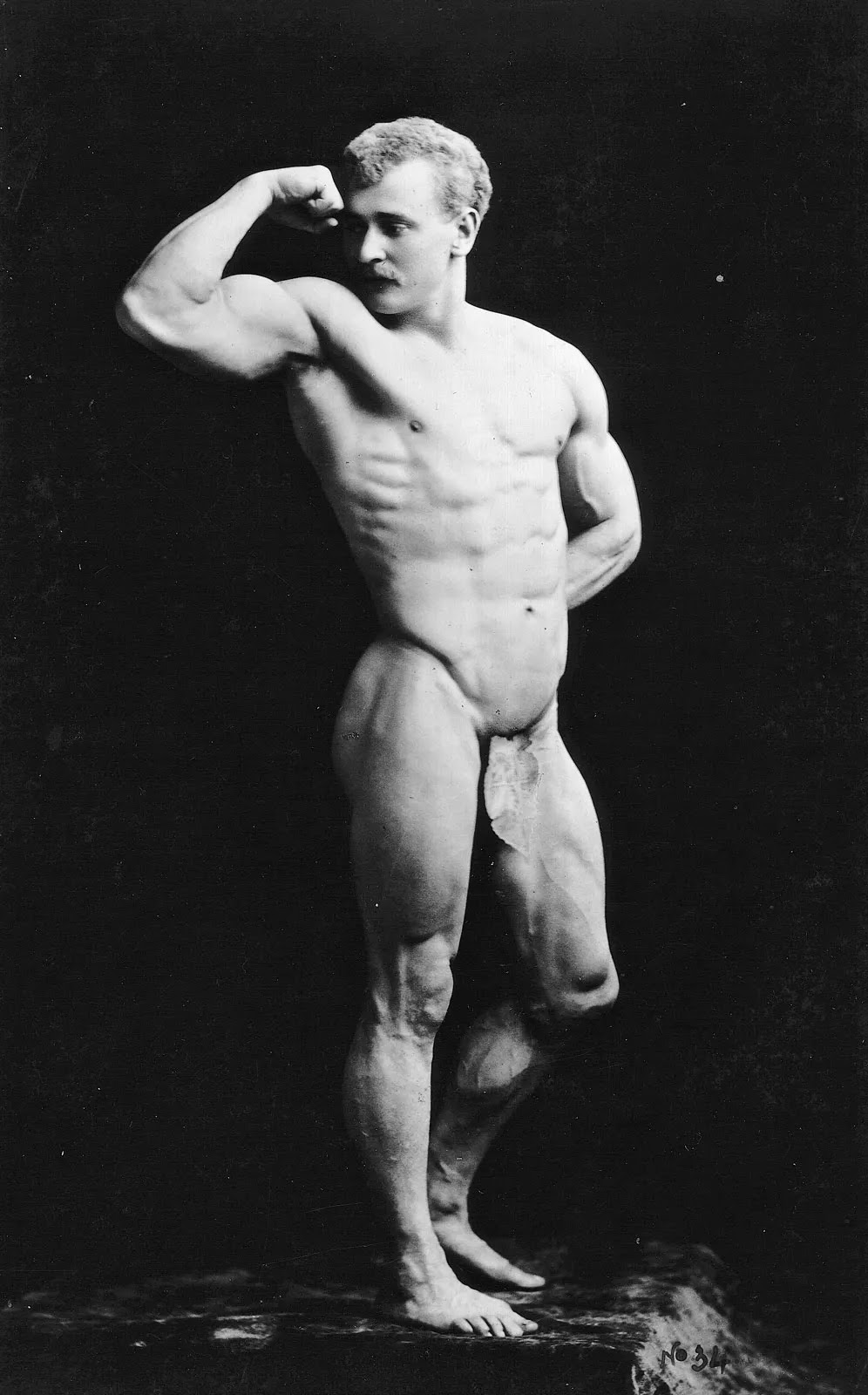

| Eugen Sandow |

[This offering can be

consumed independently BUT, it is best read as a companion to the blog/podcast

titled Three Old School Principles You MUST Have to Un-Stick Your

PT. Following this a browse of any of our old school Unleaded Conditioning

articles will add bolstering support. Surface understanding serves no good

purpose.]

Performance

Cars & Performance Bodies

We start our engines

at Le Mans, France where beginning in 1923, world class drivers came to test

themselves in a 24-hour endurance race.

Where many races are

tests of speed over a course of limited laps, Le Mans ups the ante and asks for

speed, of course, but also endurance of both the car and tests the stamina of

the flesh and blood piloting that car.

For any who doubt that

performance driving is a physical endeavor, might I suggest enrolling in a

Rally Driving Course, put yourself mid-pack at speed for even a mere 10 laps, I

wager your estimation of the physical demands will change.

All Weight Impacts All Performance

Let us turn to an

extract from an article from a 1957 issue of True magazine

titled “The Man Who Inherited Death” penned by Erwin C. Lessner. The

article discuses the in-depth preparation for Le Mans by driver Pierre Levegh.

“The petrol tank

was a large problem on Le Mans cars. Regulations set the minimum interval

between refueling at 25 laps (about 210 miles.) The Talbot had a 40-gallon tank

which gave it a basic range of 300 miles. Levegh thought that 330 would be

safer, so a new tank containing 44 gallons was built in. This in turn caused an

increase in weight. Since every ounce might

reduce speed by one yard per hour and the loss of 24-yards could decide the

issue, weight had to be saved by the body.”

Allow me to repeat that

mighty significant portion: “Since every ounce might reduce speed by

one yard per hour and the loss of 24-yards could decide the issue, weight had

to be saved by the body.”

A loss of one yard per

hour, 24-yards in a day.

One ounce could be THE tipping point in a

24-hour race.

Let’s

expand the timeline of one ounce of overage.

If it were possible to

drive that car for seven days straight that is a loss of 168 yards.

If we drove it for a

year: That is 4.96 miles.

Keep in mind we are

talking a mere single ounce.

There are 16 ounces in

a pound.

A pound of weight over

optimum results in a loss of 384 yards in a 24-hour period.

In short,

weight MATTERS.

It matters far more

than a short-term view assumes.

“Neat racing story,

Mark, but does this ounces analogy hold for living organisms?”

The

Incident of the Slightly Chubby Dog

|

| The Formerly Larger Hound in Training |

I have a Lab mix, her

name is Tu’ Sarr’i.

In December 2022 she weighed

87 pounds.

What was, as a pup, a bundle

of bounding frolicking obsessive ball-retrieving energy had, over the course of

seven years devolved to a slower ball-retrieval with a bit less obsession.

Add to it, a noticeable

limp after some play sessions.

The limp progressed to

the point where she could not walk up the stairs on some days.

A vet consult decided

surgery.

A specialist was

called in to do the surgery. He examined her and said, “Hmm, let’s try this

first—cut her weight to 75 pounds.”

At seven years old and

87 pounds she carried 12 pounds above optimum weight.

As she ages chances

for injury increase, speed goes down, stamina foreshortens.

She had been 87 pounds

for at least 3 years—the limp was not persistent, the loss of energy was not persistent—just

when it was present, it was noticeable and clearly detrimental.

Her weight overage, he

explained, was less about the impact of “Right now” than it was “Here’s

what this weight does over time by being carried every minute of the day.”

To forestall a

diminishing hip-joint, my orthopedic vet has offered that for every lost ounce

that approaches the optimum weight: performance will increase, pain will

decrease, and odds look better on the longevity table.

We dropped her weight

in 30 days.

She is drug-free, we

kept $4,900 dollars in the bank, and the dog has returned to spitfire energy

and almost annoyingly incessant prompts to play.

All resulting from trimming ounces and pounds from

the chassis that is her living performance car.

It seems

that what holds for performance cars holds for performance animals.

And for those of us

who consider ourselves combat athletes, or merely humans walking around on the planet

subject to the forces of gravity, we are performance

animals.

Keep in mind, the game

is not one of mere pounds, but even ounces in the long-haul of life.

Every increase over

optimum, well…

·

Increased

stresses on the overall structure/chassis of our bodies.

·

Decreased efficiencies

in the biochemical power-plant/fuel-injection system that is our bodies.

Fat-Shaming?

Nah, Old School Shames All

Often today’s “jacked”

is a game of increase,

That is, increasing

the size of the fuel tank with zero consideration of what the added weight

might be doing to the chassis and internal combustion engine as a whole.

Human Fuel

Tanks of Yore

If we look at athletes

of the past, or beyond sports to the conditioning of high-performing Hosses of

yore we see the ranks populated less by the comic book expectations we

encounter today than a more reserved, more realistic, more, well, I’ll say it,

efficient and effective performer.

Yes, the very large

strong man was admired and ogled, Louis Cyr comes to mind as our stand-in icon

of this class but…most of these plus-sized humans were, well, exactly that, a

bit on the plus-size. Not exactly aesthetic wonders, but one need not be an

aesthetic wonder to be effective.

If we look to the

ranks of physical culture, and/or the combat sports of boxing and wrestling we

will allow three exemplary individuals to stand-in for what was the average

“large” size of each endeavor.

Keep in

mind, these stand-ins were not outliers, they were pretty much the standard.

In physical culture we

have Eugen Sandow, coming in at 185 to 195 pounds.

A far cry from today’s

heavyweight bodybuilding class, yet, have a look-see at his physique and decide

for yourself if, “Yeah, but only if he were bigger would he be more pleasing

to the eye.”

[Keep in mind, Mr.

Sandow was not mere show-muscle, he could perform feats of strength and agility

as well. The aesthetic standard of yore also assumed ability—not mere, beach

muscle. Use-Of muscle was the watchword.]

In boxing, Jack

Dempsey, a heavyweight champion ranging in fighting weight from around 183 to

193—again a far cry from many of today’s heavyweights, yet, does anyone doubt

his formidable punch?

In wrestling we have

Jim Londos. In the puffery that often surrounds pro wrestling he was usually

billed as weighing 200 pounds, but athletes in the know who stood alongside

him, men such as David P. Willoughby, assert his weight as around 175 pounds.

[Londos, at a height

of 5’ 8”, and a gander at his physique, Willoughby’s eyewitness estimation

sounds far more in line with truth.]

The

Training Arrow of the time was, forgive the word, weighted towards natural

bounds and good performance weight.

This

lighter, by current standards, Training Arrow was nothing new to the minds of Americans

who were still steeped in the Frontier Tradition.

At the turn of the

century before the one we are examining, the 1700s to 1800s, the voyageurs

[rivermen] were considered Hoss athletes and were offered as physical exemplars

in tale after tale of remarkable feats of strength and endurance.

When frontier rivermen

are portrayed in film we often see large burly Hosses, as if that was what it

took to “get the job done.”

In fact, smallness was

coveted—a fact of economics, performance car strategy. Room in canoes was

valuable—larger men ate up room for stackable profits of beaver pelt. The

average size was closer to a height of 5’6” to 5’8” with weights topping at

around 165 pounds.

Young boys who

idolized these Rivermen often lamented growth spurts as it took them out of the

range of those they admired.

|

| Livin' at the Cut |

Leaner

& Meaner

The Training Arrows of

yore emphasized leaner means meaner not bigger is better.

Weight, be it muscle

or flab—requires resources to move. Requires energy to shuffle about the

planet.

Ounces be it muscle or

fat still impose the same performance costs over time.

The Performance Car/Slightly

Chubby Dog Analogy Holds.

Modern

Warriors Know Ounces Matter

Let us look to Marine

Owen West of 1st Force Reconnaissance Company, to illuminate. Here he refers to

a “swole” Marine.

“He has

sculpted the perfect build given our working uniform: Like cops, it is protocol

to beef up the biceps to fill out the rolled camouflage sleeves. When our

Marines start pulling this crap—working on beach muscles for aesthetic

purposes—Gunny and I run the extra meat off until they view the extra weight as

a burden.”

Start At

the Cut

This leaner = meaner

equation also applied to combat sports where weight cutting is often part and

parcel of the game.

Formerly less ado was

made about weight cutting as work-rate and frequency of fights/bouts served as

checks on between-bout bloating.

Fighters worked closer

to their natural weight class simply because, weight cutting steals strength

and stamina and winds up being a long-term drain on health.

It is akin to

attaching a U-Haul trailer to your Le Mans car between races and putting that

performance engine under stress and expecting it still to be top-notch each

time we unhitch the trailer and require it to hit an endurance track.

Start at

the cut, live at the cut.

This Training Arrow is

opposite today’s beef up and then cut down mentality.

This was seen as

counter-productive and health-killing.

Life like

Le Mans is a long-haul event.

It is a game of ounces

or pounds, where the “Yeah, I’m a few over but that’s OK” may, in fact,

matter far far more than we realize.

It matters in cars,

aircraft, elite ocean-craft, spacecraft, all vehicles expected to perform.

It matters in dogs if we

want to keep them healthy and pain-free over the long haul.

And, well, it matters

for you and me.

Every

ounce over optimum, be it muscle or fat results in a net loss over time.

The 24-hour period of

Le Mans shows us that that time scale need not be a lifetime, we may be

suffering net losses in the day to day that grow foreshortened with each day

the overage persists.

I will repeat a

portion of that, ponder it hard: We may be suffering net losses in the day

to day that grow foreshortened with each day the overage persists.

For those who may be

asking, “What’s a good target walk-around fighting weight for my height and skeletal

frame, Mark?”

We’ll

address that soon in Part 2, and it has nothing to do with the dubious BMI

scale.

But…I warn you, it

still might be lower than you’d expect.

Ounces can impede in

the short-term race.

They can kill in the

long run.

So, do you, will you,

do you wanna measure up?

[For PT constructed on

the trajectory of the Old School Training Arrow see our Unleaded

Conditioning Volumes. Available volumes include:

·

Unleaded:

Old School Conditioning The Chest Battery

·

Unleaded:

Old School Conditioning--GFF Volume 3A: Scattergun Muscle

GFF—Grip/Fingers/Forearms

·

Unleaded:

Old School Conditioning Volume 2B: Stabilizing Muscle—Hips & Thighs

·

Unleaded:

Old School Conditioning Volume 2A: Stabilizing Muscle—The Trunk

·

Unleaded:

Old School Conditioning Volume I: The Pliant Physique

·

Unleaded:

The Back Battery

·

Unleaded:

The Shoulder Battery

With more on the way!

For more Unleaded

Conditioning info see our store!

Thinkin’ about

becoming part of the Black Box Brotherhood?

Well, good on you!

Mull these resources,

Warriors!

The Black Box

Warehouse

https://www.extremeselfprotection.com/

The Rough ‘n’ Tumble

Raconteur Podcast

https://anchor.fm/mark-hatmaker

Comments

Post a Comment