When one thinks

knife-fighting, or tomahawk fighting, usually the mind drifts to a simulacrum

of tit-for-tat sword adaptation or cobbled together “sets” purporting to be “This

was how it was done, chilluns.”

This kinda-sorta-but-not-really-fencing

misses the mark by far.

This thinking is weapon-before-the-horse

territory.

By that I mean, we

often become weapon-focused, we tunnel on the implement and often fail to see that

in the beginning of man’s adoption of any tool there was an intent, a problem

to be solved and the tool was developed to resolve this problem or exercise

this intent.

That is, “I need to

accomplish so-and-so task, how can I effectively do so with what is at hand?”

Rather than, “I

have this tool in hand, I can do this with it, and I can do that with it, and

if I flip it this way, I can do this with it” in endless drum majorette

iterations.

A Plains

Example of Beyond the Edge

Let us now look to an

eyewitness account of a Lakota buffalo hunt witnessed by Francis Parkman during

his tour across the Plains.

[Be advised, the

extract is of its time and his use of descriptors no longer palatable.]

“Many of the

Indians rode at full gallop toward the spot. We followed at a more moderate

pace, and soon saw the bull lying dead on the side of the hill. The Indians

were gathered around him, and several knives were already at work. These little

instruments were plied with such wonderful address that the twisted sinews were

cut apart, the ponderous bones fell asunder as if by magic, and in a moment the

vast carcass was reduced to a heap of bloody ruins. The surrounding group of

savages offered no very attractive spectacle to a civilized eye. Some were

cracking the huge thigh-bones and devouring the marrow within; others were

cutting away pieces of the liver and other approved morsels, and swallowing

them on the spot with the appetite of wolves. The faces of most of them,

besmeared with blood from ear to ear, looked grim and horrible enough. My

friend the White Shield proffered me a marrowbone, so skillfully laid open that

all the rich substance within was exposed to view at once.”

I call your attention

to the phrase “several knives were already at work. These little instruments

were plied with such wonderful address that the twisted sinews were cut apart,

the ponderous bones fell asunder as if by magic, and in a moment the vast

carcass was reduced to a heap of bloody ruins.”

This telling

observation of facile use of “little instruments” calls attention to the fact

that often Plains inhabitants used either “made knives” [that is, blades of

stone or bone of cast-off iron] or “trade knives” that is knives bartered for

from Anglos going west.

These blades were

considered subpar and only suitable for trade with, again Parkman’s words,

“savages.”

Parkman’s account, and

many many others echo his observation, that much facile ability is made with

blades considered “not up to snuff.

He witnessed, skill of

use that was beyond the technology of the edge in hand. An intellect that saw

how to dice, slice, sever, dissect etc. An intelligence more about what

the blade will be applied to than the technology in hand.

Parkman had seen able

long hunters with their usual three-knife rig, that is belt knife, leg-knife

and patch knife.

He had seen skilled

men perform the same field dressing of buffalo with so-called better tools.

Those of what some

would later call the “Chicago way” of skilled butchery still tout the ability

and speed of these tribes with lesser tools.

What we witness with

Plains Knife Work is akin to the complete and utter creativity and utility that

was put into the buffalo itself.

You take the resource

you have [the plains knife] and find every possible manifestation of use, even

with what in many cases would be considered a “lesser tool.”

Plains knife use is

less about the tool itself, than it is about the pragmatic know-how of just

where to insert, slice, hack, tear, approach, grip-flip, heel-back, thumb-down,

twist, tuck, and all the other subtle ways of making full and complete use of a

single knife.

And so little of that

use is reflective of the mano y mano dueling approach transported with a

Toledo steel mindset.

Necessity, creativity

and survival forged this approach.

Necessity, creativity

and survival created an astonishing fount of bladed wisdom.

These tactics were

designed to work with lesser blades, and thusly work beautifully with our

modern cutlery.

It calls to mind

Seneca’s observation:

“He is the great

man who uses the earthenware dishes as if they were silver and he is equally

great if uses silver as if it were earthenware.”

Plains knifework is

silver-plated earthenware and well worth resurrecting.

South of

the Border Beyond the Edge

Knife fighting styles

differed according to broad geographic region, a point we have already digressed

upon. North of the Border we have indigenous tribes wielding subpar blades with

facile ability.

South of the Border we

see a rise in blade quality, but we still see the same appreciation for the what

and how of where the blade is to be applied.

The Southern Knife

vocabulary for thrusts, slices, hacks, butts et cetera is mirrored by an

equally deep vocabulary for what is to be thrusted into, sliced, hacked,

butted et cetera.

Some of this vocabulary

echoed into the matador tradition well into the 1940s.

A few examples…

Pinchazo-An ineffectual thrust.

Pinchazo

soltando—A thrust that strikes

bone and falls to the ground.

Or the worst insult of

all---Pistola! Which implies that the knife-wielder is so inept that

they would be better off killing with a firearm than a blade.

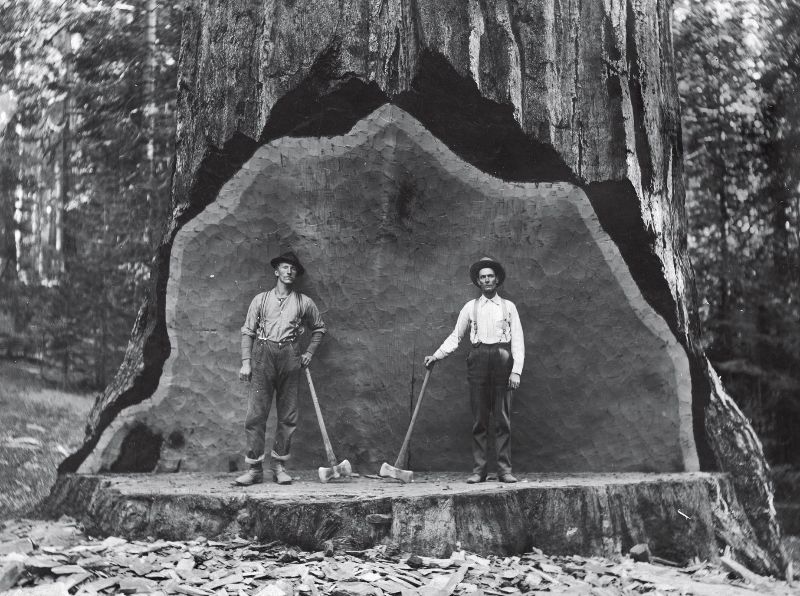

‘Hawks

& Axes Beyond the Edge

This beyond the edge

wisdom is found in the swinging edge as well, be that a tomahawk, a boarding

ax, a broad ax, or a battle-axe.

We have already

belabored how any knowledgeable ax wielder worth their salt “hangs” their ax

and tests it with a single line of twine to truly know the “set.”

These tests are done

with any new swinging implement to get maximum application out of it.

[See our DVD Battle

Axe Secrets for details.]

Beyond the

Edge: “Seeing” Limbs

Just as earlier

cultures had at least rudimentary butchery skills, that allowed for basic knowledge

of where to joint, separate, divide and sunder a formerly living carcass…

Lumberjacks, woodsmen,

hell, any homesteader who had to cook or keep warm knew how to see a tree.

Thought

Experiment: If I asked you to

approach two trees to chop both down, limb them for me, then section them for

the stove.

One tree

is a conifer the other deciduous, would your tactics change?

When I ask most this

question, a trap is sensed so the wary is answer is “Maybe.”

If I hadn’t asked

about tactics most would just chop willy-nilly at both trees with no difference

in approach.

That same question asked

of a frontier woodsman would be answered, “Why, of course, there’s a

difference. You callin’ me a Fool!”

And what would this

differing strategy be, you may ask.

Beyond the

Edge: Reaction Wood

Protruding limbs

require bolstering to remain in fixed positions.

Most limbs do not grow

willow like and sag, most are the fixed sturdy limbs of tree climbing fun.

Conifers and deciduous/broadleaf

trees use two different strategies to support limbs.

There are only two

ways for trees to approach this engineering feat…

One-They can bolster more support material above

the branch, that is pulling the branch upward—called Tension Wood in arbor

science.

Two—They can deposit more structure beneath the

branch and push it into a fixed position—this is called Compression Wood.

Broadleaf trees use a

Tension Wood strategy and Conifers a Compression Wood strategy.

On our next forest

walk we can recognize these strategies in a heartbeat by noticing the slight

bulges above or below branches where they join the trunk.

Our wise ax swingers

and limbers do not need the extra work of cutting through thicker more

bolstered wood fibers so when approaching a broadleaf they see it as a below the

branch approach [away from the tension bulge] and above the limb strategy for

the conifer.

The same reading of trees

applies when hacking though a jungle, blazing a trail—read the bulges and swing

accordingly.

Beyond the

Edge

Be it wielding knife,

ax, ‘’hawk or any other bladed implement, those before us, before the era of

weapon-tunnelling possessed many complementary skills that allowed them to bring

to bear more wisdom to the tool in hand.

Butchering strategies

are copious. Wood-Reading strategies equally so.

The eyes that can read

these terrains, both are living tissues after all, can better wield the tool in

hand.

Be that to build a

fire, to joint a deer, or to unlimb an opponent Viking style.

There is far more

beyond the edge than there is in the edge itself.

For more on Old School Edge Work, see The Black Box Volumes—this month features Pirate Boarding Ax Tactics.]

[For more Rough& Tumble

history, Indigenous Ability hacks, and for pragmatic applications of old school

tactics historically accurate and viciously verified see our RAW/Black Box Subscription Service.]

Or our brand-spankin’ new podcast The Rough and Tumble Raconteur

available on all platforms.

Comments

Post a Comment