Today let’s take a journey from the ancient

Olympics, stop by Denmark for some Viking practices, sojourn with the Inuit and

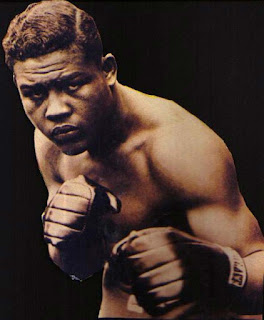

Chippewa cultures, and steal an idea or two from the boxing heavyweight great

Joe “The Brown Bomber” Louis.

Today let’s take a journey from the ancient

Olympics, stop by Denmark for some Viking practices, sojourn with the Inuit and

Chippewa cultures, and steal an idea or two from the boxing heavyweight great

Joe “The Brown Bomber” Louis.

First, let’s define our terms.

By movement under load training I refer not to

weight lifting but the conducting of your sport/training with additional weight

or added resistance hampering your standard movement in the aid of increasing

performance once the limiter is removed.

Let’s start with the ancient Hellenes.

In the original incarnations of the Olympic

Games, the jumping events, standing broad jump, running jump, clearing obstacle

et cetera were conducted with devices called halteres. Halteres were bits of stone or metal loosely shaped like

a modern dumbbell.

The athlete would grasp the two ends of the haltere and use a swinging momentum of

the arms to “assist” the jump without ever releasing the device. It was thought

that halteres would increase strength

and difficulty.

It does--In my own experiments with mock haltere [grasping a dumbbell] my

swinging jump coordination leaves much to be desired, and the landing g-forces

left me leery of attempting maximal efforts.

However, no less a personage than Aristotle in

his On the Movement of Animals states:

“A pentathlete using halteres jumps farther

than one without them.”

Gradually these devices faded from being used

in the games but were still used in the training of the jumpist. [An archaic word

I have grown fond of.]

Next cultural stop—the fjords of Scandinavia.

There are numerous refences in the sagas to

Vikings training in knee and waist high water. They would run, jump, and engage

in mock combat in this depth to both garner strength and to train in conditions

they were likely to encounter in storming beaches.

There are numerous references in the anthropological

record of Northern tribes, the Inuit and Aleut among them, competing in running

and sprinting in various depths of snow. Here the snow acts in the same resisting

manner as does the melted form in the Viking counterpart of the training.

American Indian tribes have a deep and resonant

history of running. Running for war training, running for escape training, and

running for ritualized purposes. Many tribes had their own form of adding resistance

to the runs, ideas ranging from partner carries, stone hauls, creek running

[the Viking idea rears its head again,] running in deep sand along dunes, hill

and mountain running, but let us look to the Chippewa tribe for a specific

device to add resistance.

As part of a tradition linked to the deity

Part-Sky Woman, runners would attach decorative weights filled with lead shot

to the bare-feet. Many miles were run with these ankle-weights, but they were

shed for tribal competition or warfare.

As part of a tradition linked to the deity

Part-Sky Woman, runners would attach decorative weights filled with lead shot

to the bare-feet. Many miles were run with these ankle-weights, but they were

shed for tribal competition or warfare.

Let’s bring it to the 20th century.

Movement underload training is still used, most

extensively by the military in the form of rucking, which has gradually made its

way to aspects of civilian athlete training.

In boxing and wrestling training there is a

long-tradition of wearing ankle-weights ala the Chippewa to add resistance to distance

runs.

But let’s look to the great Joe Louis for two

ways, one standard, and one less so, that he used to assist his long tenure as

heavyweight champion of the world.

The Brown Bomber did his Rock-Runs [we will

play with Rock-Runs another day] in a pair of heavy boots. His trainers, Jack Blackburn

and Mannie Seamon, made it a point to select heavy boots for roadwork. The heavier

the better.

Another less expected practice to build sport

specific resistance—a thicker than average padding beneath the canvas of Louis’

training ring.

Another less expected practice to build sport

specific resistance—a thicker than average padding beneath the canvas of Louis’

training ring.

Seamon regularly added ¾” of padding to the standard

padding depth so that Louis was working against resistance in both movement and

power throughout his training. Seamon felt that when it came to fight night it

gave the champ added snap to his punches and made his movement lighter more

akin to a middleweight.

I can testify to a bit of that. I use a double

layer of reselite wrestling mats for training, and when stepping onto a single

layer it feels absurdly fast.

There are many more examples from history, cultures,

and individual athletes of movement under load training, but the offered instances

should give us a healthy respect for the practice and perhaps cause us to consider

adding a few of these ideas to give our own training, giving it a bit of historical

heft.

Comments

Post a Comment